A Serious Rival to String Theory and Loop Quantum Gravity

For a century, the deepest questions in physics have been framed like a one-way street: classical mechanics ends, quantum mechanics begins, and relativity sits on a separate throne.

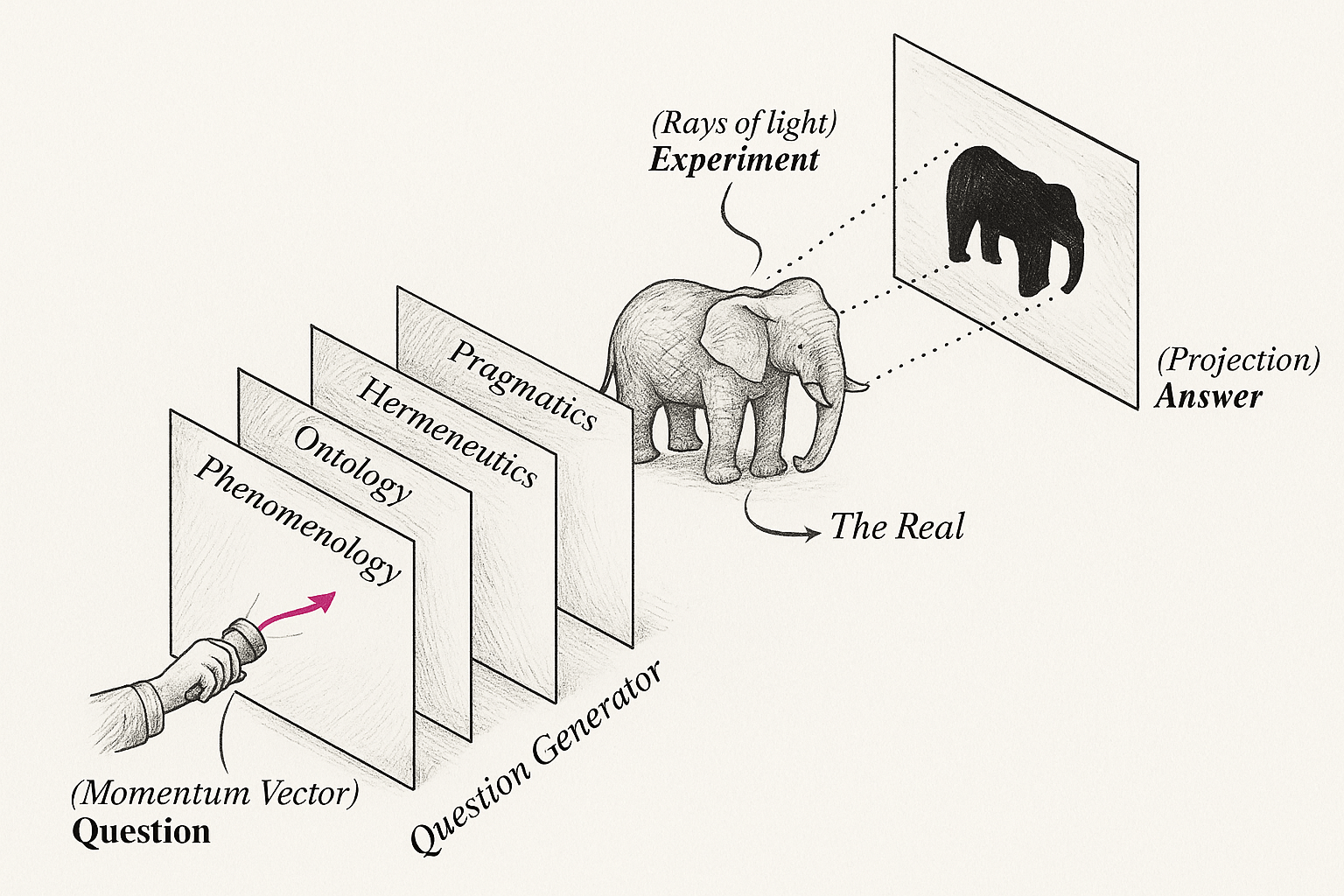

The modern “frontier” then becomes an arms race of complexity—extra dimensions, abstract topological networks, renormalization machinery, and interpretational fog that even experts struggle to explain without hand-waving. And yet the uncomfortable truth remains that the biggest mysteries are still open: why the electron has its mass, why α has its value, why QED needs infinities tamed by renormalization, and why gravity refuses to sit comfortably inside the quantum world. If physics is honest, it must admit that elegance alone is not enough—what matters is whether a framework and .

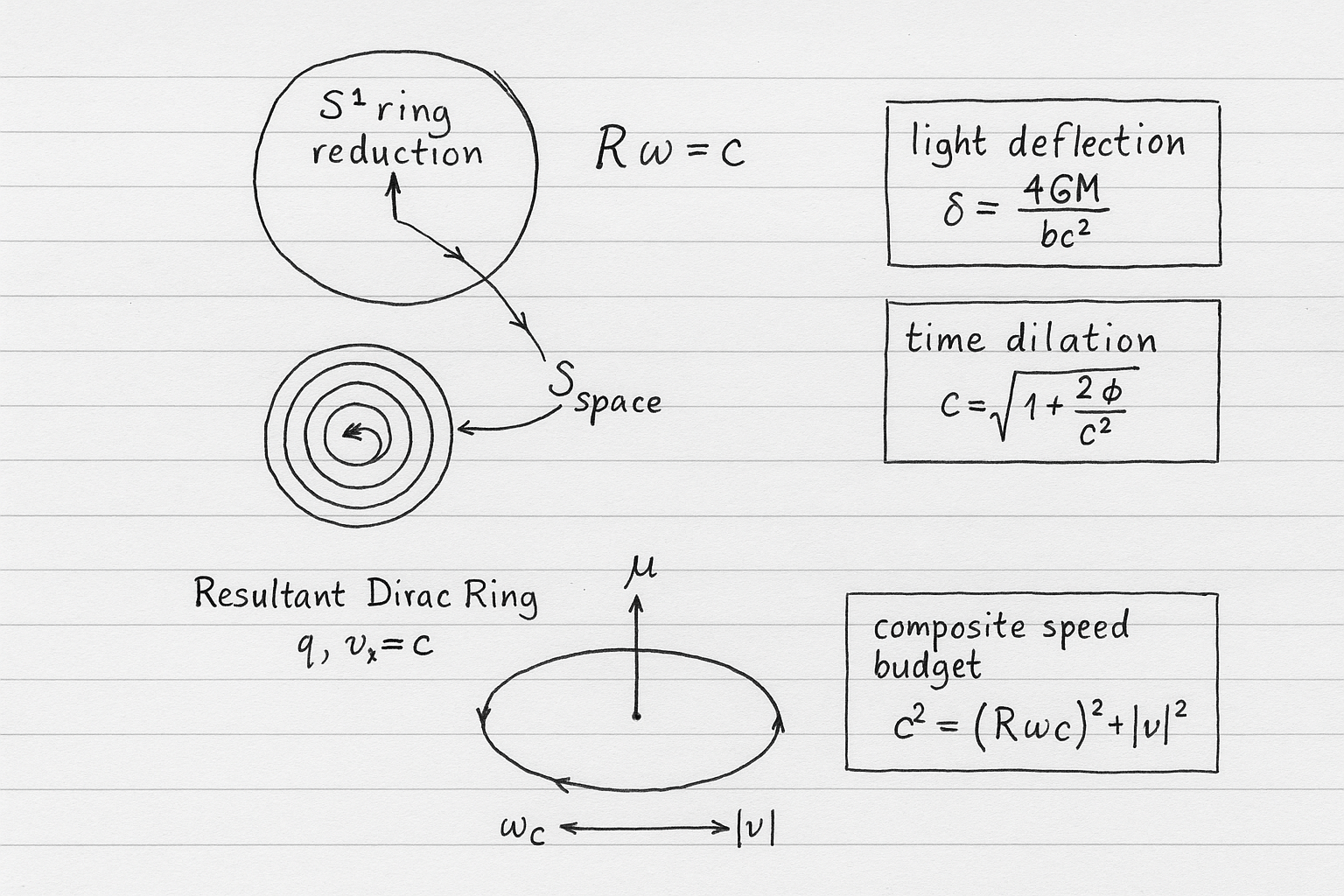

In 1928, Paul Dirac forced the relativistic energy relation into a Schrödinger-like structure, and it detonated an intellectual revolution: spin emerged, antimatter appeared as a prediction, and matter itself became deeper than anyone expected. That move is a reminder that foundational progress sometimes comes from a dangerous kind of simplicity—one constraint, one re-framing, one unification of languages that were assumed to be incompatible. Dirac did not “decorate” physics; he rewired it. Relator theory is written in that same spirit, but it walks a different direction: instead of making Schrödinger relativistic by replacing it, it asks whether classical Schrödinger dynamics—paired with a strict kinematic lock—can generate the relativistic and gravitational phenomena people assume require SR/GR as axioms.

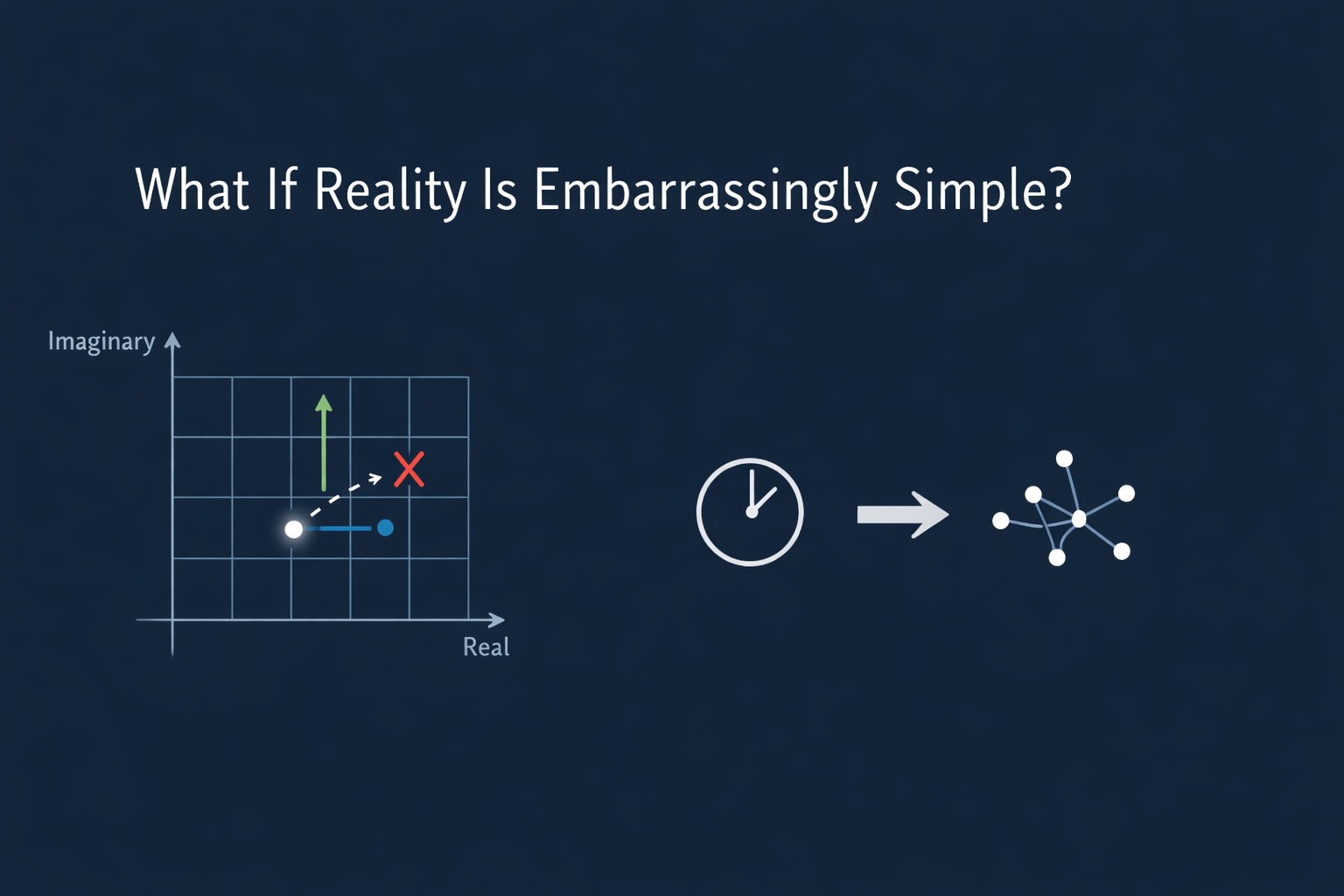

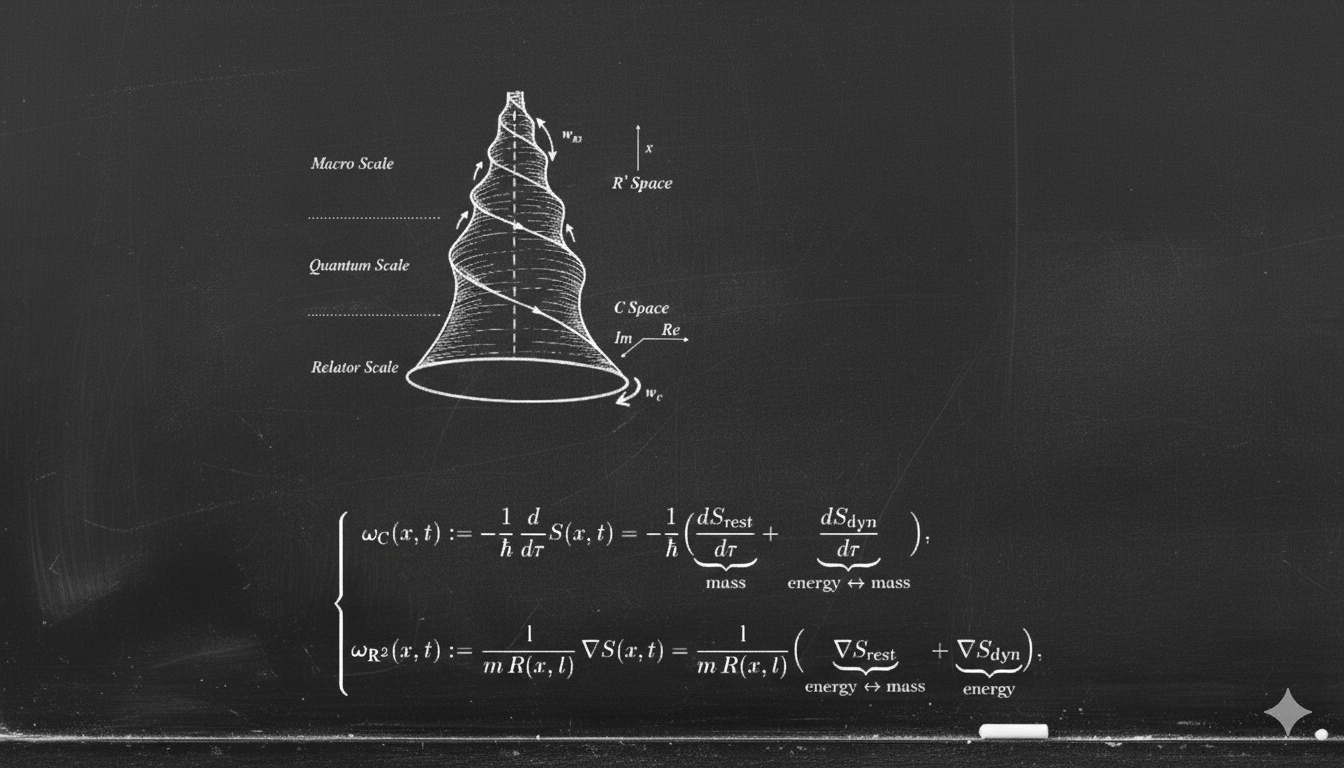

Relator theory claims something that sounds illegal to the trained ear: classical and quantum are not enemies, and quantum is not a rupture from classical physics, but the of it under an overlooked constraint linking evolution and phase. In this picture, you don’t start by postulating 10/11/26 dimensions, or by quantizing geometry first, or by declaring spacetime fundamental. You start with a minimal principle, force the mathematics to be consistent, and let the observed phenomena fall out as consequences—time dilation, gravitational time dilation, redshift, Shapiro-type delay, even light deflection—without importing SR/GR as the foundational starting point. This is not presented as a metaphor or a vibe; it is presented as a derivation that can be read, attacked, or refuted line-by-line.

What makes this approach a serious rival—rather than another “interpretation”—is that it aims at the hardest targets: fundamental constants and precision observables. Relator theory asserts that quantities typically treated as inputs or experimentally fitted parameters can be computed from structure: the electron mass (and lepton scale more generally), the origin and value of the fine-structure constant α, and even the g-factor without leaning on the traditional QED diagrammatic machinery and its renormalization culture. It also claims to bring gravity into the quantum framework in a way that avoids the usual divergence story—not by sweeping infinities under the rug, but by building the theory so the rug isn’t needed. That is an audacious claim, but audacity is not the issue; the only issue is whether the math stands.

Of course the first reaction most people will have is: “This must be crackpot physics.” And frankly, that reflex is understandable after a century of proposals where the gap between formalism and physical clarity has grown so large that even professionals can’t translate the story for ordinary scientists, let alone the public. But skepticism has a proper format. Skepticism is not a slogan like “Schrödinger isn’t relativistic” thrown as a spell to avoid reading; skepticism is a scalpel that points to a specific line, a hidden assumption, a broken invariance, a missing boundary condition, a contradiction in limits. If you are truly confident it’s wrong, then reading it should be easy—because you’ll be able to name where it fails. If you refuse to read it, that is not rigor; that is fear disguised as taste.

There is also a psychological reason the resistance will be intense. A minimal framework that claims to answer questions that string theory and loop quantum gravity have not conclusively answered threatens more than ideas—it threatens careers, identities, and intellectual investments. This is an old story in science. Planck’s bitter observation still echoes: new truths often don’t win by persuasion; they win when a generation changes. I expect exactly that kind of resistance, and I don’t romanticize it. It may take twenty or thirty years before a clean evaluation becomes culturally possible. But I’m also betting on a simpler path: that among thousands of physicists and students, a small number will read carefully, test the steps, and respond like scientists instead of gatekeepers.

So here is the challenge, stated plainly and without theatrics. Don’t argue with labels. Don’t debate the vibe. Don’t protect the temple of what you were taught. Read the derivation and do the only two honest things available: refute it precisely, or admit it deserves serious attention. Because if Relator theory is wrong, it can be killed properly with mathematics—and that’s a service to everyone. But if it is right, even partially, then it is not a minor correction to modern physics; it is a shift in the meaning of “foundation,” a rewiring of how classical, quantum, and gravitational phenomena relate. And that is exactly why it deserves to be read.

Make Your Business Online By The Best No—Code & No—Plugin Solution In The Market.

30 Day Money-Back Guarantee

Say goodbye to your low online sales rate!